harry potter and the curse of dimensionality

john von nuemann was once quote to say that “in mathematics you don’t understand things, you just get used to them” (this quote hung on my monitor throughout grad school). one of my favorite examples in support of this quote has to do with high dimensional euclidean spaces, and was taught to be by none other than nakul “the prince of darkness” verma. it’s a particularly good reality check for those who wish to partake in “data science” but don’t realize how misleading human intuition can be.

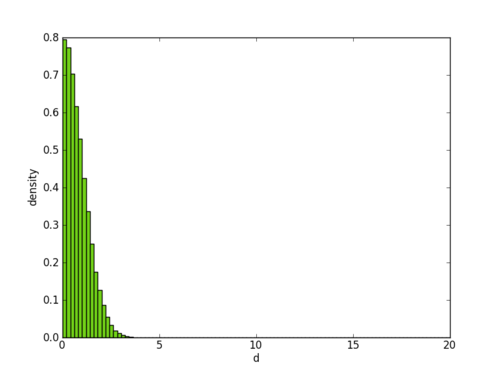

it goes something like this: take a one dimensional gaussian distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1: x ~ N(0,1). now, define another random variable d = ||x|| (for now x is a scalar so ||x|| = |x|). in other words, d is the distance between a random point drawn from the gaussian and its mean (because the mean is at 0). now, the question is: what does the distribution of d look like? here’s the answer:

nothing surprising, right? most of the points x will be close to the mean, and so most of the distances will be 0 or close to 0.

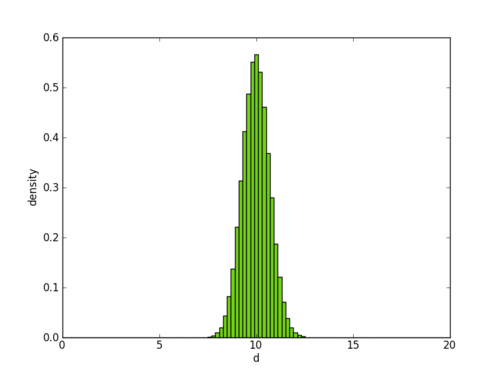

now try the same exercise, but this time with x coming from a 100-dimensional gaussian (x ~ N(0, I), where Iis the identity matrix). define d the same as before, and now think about what the distribution of d should look like?

i’m guessing most people will not guess the following:

but that is in fact the correct answer (fire up python or matlab and double check yourself). a high dimensional gaussian distribution “looks” like a hollow sphere!

so why on earth does it look like that?! being a “punk statistician”, i’m probably not the right person to answer that question, so my official response is: see the von neumann quote above :)

but if you allow me to be hand wavy for a moment, here is how i rationalize this to myself: think about a cube in 3 dimensions with sides length 1. it has 2^3=8 corners, and volume 1. now think about a cube in 100 dimensions with sides length 1. it has 2^100=“a lot of” corners, yet the volume is still 1. now, the volumes are not directly comparable because the dimensionality is different, but the high level idea is that the number of corners blows up exponentially as dimensionality increases. in a high dimensional cube most of the volume is in the corners (simply because there are so many of them). so, going back to our gaussian distribution, even though the mean has the highest density, the space around the mean is insignificant compared to all “corners” of the high dimensional space, so most of the point fall far away from the mean.

so there you have it: a fairly straight forward question, and a completely unintuitive answer. human intuition, especially with regard to geometry, is finely tuned to 3 dimensions and it is only through practice that one can build appropriate intuition for many concepts in math.

by the way, here is a more rigorous look at the same phenomenon.